First Story:

"My grandfather served in the Civil War. He was underage. He was a drummer boy."

Relative of Patsy: "According to X, underaged soldiers would put 21 on a piece of a paper in their shoe so they could be over 21..."

"After the war, he was in Chicago when Lincoln came through (assuming his funeral procession). At the end of the war, grandfather destroyed the drum because he never wanted to see it again."

Later in the tour:

Relative: "Tell him about the tin, Aunt Patsy."

"One afternoon my grandmother was carrying this tin full of black currants to the cellar to keep cool. As she was heading down the stairs, a man appeared and asked her 'are you Widow Chandler?'"

" My grandmother said no, 'I'm Mrs. Chandler'"

"He said, 'well are about to be Widow Chandler. Your husband was nearly killed at the mill today.'"

"My grandmother would always say in a dramatic, breathless fashion, 'It was like my corset was being tightened and I couldn't breathe.'"

"What happened was my grandfather and the crew were cleaning up. One of his co-workers hit a switch with his broom. The switch turned on the saw. The carriage knocked him over and carried him into the blade. He lost his hand and leg."

"They brought him home, and the neighbors put up sheets in his room and threw buckets of water on them to keep the house cool."

"They thought he was going to die, but he lived. He became the City Treasurer eventually. As he was a Civil War veteran, my grandmother didn't have to pay property taxes. He was the drummer boy.She could never look at that tin or smell black currants without recalling all of this."

Recorded later in the tour:

"My grandfather had a hook as his hand. He would cut his meat using the hook to hold down the plate. The table they ate on had his hook marks on it. Another time he was walking home in the winter and got his peg leg stuck in a hole. So he decided to not walk in the winter anymore. As he walked to the barber, my grandfather went all winter without getting his hair cut. He let the girls braid his long hair and put yellow ribbon in his hair. His barber was on 4th street, and everyone turned out to laugh at his ribbons and braids before he got his hair cut."

"Grandpa always described William Young like this, "After every dinner, he would get a pencil and sign the

tablecloth with large script to make sure that the staff properly washed the tablecloth."

Patsy wrote her family a letter as the ghost of E.B. Chandler. In the letter, she mentioned that he went from Sherman's March to the Sea to a Clinton Iowa Sawmill Worker to the City Treasurer.

Transcribed by Patsy X on November 15, 2013 at 2:30pm

Notes:

According to the local and therefore usual historical books:

The grandfather was Esek B. Chandler. He was born in Perry County, Illinois in 1844. Chandler's family lived in Whiteside County and Albany, Illinois. At 17, he joined the army supposedly. Perhaps sometime in the 1870s, E.B. started to work as a sawyer. In 1881, his accident happened. He was elected as treasurer in 1908 and 1910.

Grandmother's name is most likely Emma.

A collection of notes, research, and mini-articles on Clinton's rich lumber history and the American lumber saga. Feel free to comment, either with corrections or with suggestions. This is a discourse.

Friday, November 15, 2013

Friday, October 11, 2013

Clinton Iowa and the First Autism Case

The first three children exhibiting autism were "a child from Forest, Mississippi, the son of a plant pathologist, and the son of a forestry professor in a southern University (Olmsted)."

The most famous first child with autism was Donald from Forest, Mississippi. In their book The Age of Autism, Dan Olmsted and Mark Blaxill talk about a new product Lignasan that was used to treat pine. One of the ingredients in Lignasan was ethylmercury.

While the authors don't prove it was a cause, one company known to partake in the use of Lignasan was the firm Eastman-Gardiner. They butted up against another lumber company who used the chemical. This company operated in Forest, Mississippi. When Donald's parents built their house, they most likely used wood from either mill to build their home. Of course, the authors are saying mercury causes autism, and that's not important here. What is important is as this product wore down it realized ethylmercury into the air. So the house was literally breathing out mercury, which the inhabitants would have been breathing. So while i probably isn't the cause of autism or more direct, this isn't the amazing part to me. I find it amazing that a firm from Clinton, Iowa moved to Laurel, Mississippi and employed a toxic chemical that 80 years later would be connected to the autism debate.

The history of the Gardiner interests is a huge undertaking. The Gardiners went from working in the Lamb mills to owning their own to moving south. In the South, they operated one of the nation's largest mills and completely transformed the town of Laurel, Mississippi. They also invested in mineral rights and oil rights in the South. I doubt they would have foreseen becoming a minor footnote in the history of autism.

The most famous first child with autism was Donald from Forest, Mississippi. In their book The Age of Autism, Dan Olmsted and Mark Blaxill talk about a new product Lignasan that was used to treat pine. One of the ingredients in Lignasan was ethylmercury.

While the authors don't prove it was a cause, one company known to partake in the use of Lignasan was the firm Eastman-Gardiner. They butted up against another lumber company who used the chemical. This company operated in Forest, Mississippi. When Donald's parents built their house, they most likely used wood from either mill to build their home. Of course, the authors are saying mercury causes autism, and that's not important here. What is important is as this product wore down it realized ethylmercury into the air. So the house was literally breathing out mercury, which the inhabitants would have been breathing. So while i probably isn't the cause of autism or more direct, this isn't the amazing part to me. I find it amazing that a firm from Clinton, Iowa moved to Laurel, Mississippi and employed a toxic chemical that 80 years later would be connected to the autism debate.

The history of the Gardiner interests is a huge undertaking. The Gardiners went from working in the Lamb mills to owning their own to moving south. In the South, they operated one of the nation's largest mills and completely transformed the town of Laurel, Mississippi. They also invested in mineral rights and oil rights in the South. I doubt they would have foreseen becoming a minor footnote in the history of autism.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

My Posts Have Been Depleted... Now Rebirth!

I apologize for the limited posts in the past few weeks, maybe months. The Sawmill Museum has been very busy, and we hope that in the next six months to have some very exciting news to share. In the next four weeks, I would expect quite a few updates.

Lately, I've been reading about the depletion of the North Woods in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan. The cries began in America in earnest in the 1860s and 1870s and reached its peak by the 1900-1910 era of Teddy, as the story goes. One of my favorite books on the subject is The Depletion Myth by Sherry Olson that sets out to examine whether the forests were really on their way out. Sherry allows for the fact that virgin timber has been greatly reduced and the monster trees of yesteryear are no more. Even more Sherry allows that a change needed to happen. The book places the consumer at the heart of the change. The "saving" of the forests happened because of a change in the economy and consumer habits. Sherry's largest point was the changes in the economics and technology allowed for more farmland to be turned over to forests. The book is a very interesting answer to the role of conservation in saving America's forests.

Just a quick story, more to come.

Sources:

http://books.google.com/books?id=hVyRyxyoOR0C&pg=PA209&dq=depletion+of+forests+wisconsin&hl=en&sa=X&ei=XfNVUuH0NIOBygH0sYDYDA&ved=0CEYQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=iowa&f=false

Lately, I've been reading about the depletion of the North Woods in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan. The cries began in America in earnest in the 1860s and 1870s and reached its peak by the 1900-1910 era of Teddy, as the story goes. One of my favorite books on the subject is The Depletion Myth by Sherry Olson that sets out to examine whether the forests were really on their way out. Sherry allows for the fact that virgin timber has been greatly reduced and the monster trees of yesteryear are no more. Even more Sherry allows that a change needed to happen. The book places the consumer at the heart of the change. The "saving" of the forests happened because of a change in the economy and consumer habits. Sherry's largest point was the changes in the economics and technology allowed for more farmland to be turned over to forests. The book is a very interesting answer to the role of conservation in saving America's forests.

Just a quick story, more to come.

Sources:

http://books.google.com/books?id=hVyRyxyoOR0C&pg=PA209&dq=depletion+of+forests+wisconsin&hl=en&sa=X&ei=XfNVUuH0NIOBygH0sYDYDA&ved=0CEYQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=iowa&f=false

Friday, August 23, 2013

Lumberjacks Gone Mad

It's tough to provide a sketch of a lumberjack. The more I read about lumberjacks, the more I realize the pitfalls of poverty, solitude, and proliferation of drugs. While some lumberjacks were transients, others had nowhere else to go. Some had no family or relatives, and other had too many wives or women who called them honey.

This article comes from another article I'm developing. The other article is about the sex trafficking that brought young girls to lumber camps to serve as prostitutes. An all too common reality of life in the camps was the presence of alcohol fueled violence and crimes. This article talks about some of the murders that made papers in the early 1900s. Papers were quick to point out two things: a. the murderer was a lumberjack and b. the murderer was a immigrant lumberjack.

This article comes from another article I'm developing. The other article is about the sex trafficking that brought young girls to lumber camps to serve as prostitutes. An all too common reality of life in the camps was the presence of alcohol fueled violence and crimes. This article talks about some of the murders that made papers in the early 1900s. Papers were quick to point out two things: a. the murderer was a lumberjack and b. the murderer was a immigrant lumberjack.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

A tale of my Raftin' Grandfather

Yesterday, a guest shared an amazing story about one of his perhaps his (great?) grandfather. The transcription of the conversation:

"William Mac Litchfield had timber rights in Wisconsin (1). He had a partner. They cut the timber, felled the logs. They floated the logs down the Wisconsin River into the Mississippi River. One bad winter, can't remember the year, there was no snow (5). They couldn't do a log drive. They had to fire people to debark the logs to stop the logs from rotting. The partnership went bust. My (great?) grandfather sold to his partner.

My (great?) grandfather continued working for his partner as a cook on the log raft. Eventually he became a carpenter in the winter and a pearl fisherman on the Mississippi in the summer. He was born in Mather, Wisconsin (6). He was born in 1838. My dad was born in 1897. I can't remember when my (great?) grandfather was a raftman, but I would say in the 1860's (5)."

Transcribed from Bill Litchfield of Charleston, SC by Matt Parbs on August 21, 2013

Notes (given the nature of genealogical research, not necessary all true:

1. Depending on the record, (great?) grandpa spelled his name both William Mac and William Mack Litchfield. While ancestry.com is not gospel, there is a strong possibility this is the William Mack Litchfield:

Henry Bruer, the founder of Bruer Lumber Company, was born in Bancroft, Iowa in 1884.

Recorded 8/8

2. William Mack died in Winona, Minnesota in 1922. He was buried in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

3. According to other documents, William and his wife came to Mowers County in 1856 and settled on a 250 acre farm in section 34.

4. According to this site, William M Litchfield shares a distantly connected ancestor to the great Abraham Lincoln.

5. Based off the literature here (http://www.tomclough.com/genealogy/p332.htm), we can say that William M. arrived in Wisconsin in time for the 1870 Census. Since this was the case, I can say with certainty that his grandfather lost his hat in 1869's "The Big Log Jam." In Weyerhaeuser's biography, there is a tale of the 1869 winter being so mild that by spring, there wasn't enough water to float the logs down the Chippewa into the Mississippi. The low waters caused 150 million feet of logs to pile up and the logs stacked 30 feet high above the river's surface. Many lost their hats in spring of 1869.

6. In 1870, it is apparent he lived in the part of Wisconsin that is now Wisconsin Dells. They lived in Kilbourn City, Wisconsin. One might suspect that his partner was his wife's husband, a Seth Burgess Wing. The Wings, along with the Litchfields, "all" hailed from VT. The Wings moved to Columbia County, WI in 1866.

William's sister, Luthera, married a Stephen Wing in 1857. He died "from exhaustion upon the march" in the Civil War in 1864. Luthera later married Seth in 1866. After their marriage, the Wings moved to WI in late 1866. One could assume that William M. followed or led.

Story Two

Another guest regaled our staff with a mini history about his family's lumber connections. His father, Earl Nielsen, grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His dad was a river raftsman. His grandfather, Samuel N. Nielsen, was the secretary and treasurer of the Bruer Lumber Company. The guest called his grandfather an owner of the lumber company, and Samuel was a co-owner. He purchased stock and became a board member of the corporation.Henry Bruer, the founder of Bruer Lumber Company, was born in Bancroft, Iowa in 1884.

Recorded 8/8

Monday, August 19, 2013

What is in this USPS Box?

Wow, what a treasure trove I stumbled upon in our filing cabinet. While looking for who knows what, I saw the USPS eagle staring up at me. Attached to the priority mail box was a simple letter from a Marilyn. I would have to guess it's the same Marilyn thanked in Felix Adler's biography.

Marilyn wanted our Bob Seger to know that "Years ago Al Bowers gave us a lot of old paper clippings. These have to do with the sawmills and log rafting, etc. I think they would be better appreciated at the sawmill museum- if they can use them somehow."

Well Marilyn, we will. I scanned all of the clippings in, and below you find my favorite quote:

"There was no tougher creature than a raftsman. His job in itself was harrowing, dangerous, and it seemed to spawn an ego of recklessness within him. On the raft, he drank hard whiskey, cursed, worked exhausting hours and never shaved and rarely bathed. Raftsmen were ribald devils, often singing or calling to the girls on the shore of the little towns they passed, and a favorite ditty (scrubbed up a bit here) went something like:

"Buffalo gals, ain't

you comin' out tonight,

comin' out tonight, comin'

out tonight."'

Marilyn wanted our Bob Seger to know that "Years ago Al Bowers gave us a lot of old paper clippings. These have to do with the sawmills and log rafting, etc. I think they would be better appreciated at the sawmill museum- if they can use them somehow."

Well Marilyn, we will. I scanned all of the clippings in, and below you find my favorite quote:

"There was no tougher creature than a raftsman. His job in itself was harrowing, dangerous, and it seemed to spawn an ego of recklessness within him. On the raft, he drank hard whiskey, cursed, worked exhausting hours and never shaved and rarely bathed. Raftsmen were ribald devils, often singing or calling to the girls on the shore of the little towns they passed, and a favorite ditty (scrubbed up a bit here) went something like:

"Buffalo gals, ain't

you comin' out tonight,

comin' out tonight, comin'

out tonight."'

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

The men who ran Clinton's Sawmills

While it is easy to be swept away by the lumber barons, one cannot forget the hundreds and thousands of men who operated the mills. Below are found sketches of the workers, mainly foremans and upper management, who ran the sawmills.

B.C. Brown: A native of NY, he came to Clinton in 1865. In 1872, he became the foreman of Young's lower mill. Brown supposedly patented a splat and shingle mill used in all of Clinton's mill.

Judson Hyde: A native of NY, he was a saw-filer in Young's upper mill. Judson served as the Secretary for the Odd-Fellows lodge. The lodge was on a Harding block in 1874 when Judson was the Secretary. He was also involved with a civic organization called Clinton Encampment, another? Odd Fellows congregation.

George T. McClure: George was the foreman for Lamb's Riverside mill.

John D.C. McClure: Sources differ, but John started as a saw filer in 1869 or 1870 for C. Lamb & Sons. He worked for them until 1883. During that time, he saw the first band saw installed in the Lamb mill. The mill consisted of, or John oversaw, two bands and two gang saws. When John started, "the science of saw filing was in its infancy" either in reference to band saws or all types of saws (B, 67). In 1883, John left for the Lyons Lumber Company where he worked for four years. In 1887, John left for the Southern mills where he became a foreman and a filer at the Woodworth Lumber Company in Bivins, Texas. He later went to Monroe, La to file. John in the late 1890s went to work for the Gates Lumber Company in Wilmar, Arkansas. Through his life, John supposedly filed saws for 55 years. He was called the South's best filer.

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~arbradle/letters/pontius_postcards.html

David W. Switzer: Born in NY in 1833, he came to Clinton in 1857 and started working in the Lamb mills. He eventually became the foreman of the C. Lamb & Son's Stone Mill. According to other notes, Switzer's daughter, Hazel Harriet Gertrude Switzer married William Mowbray Browning in 1902. Hazel was apparently known as Effie?

John Taylor: John worked for the William J. Young & Co as their machinist foreman. Born in NY, John learned his trade in Worcester, MA.

W.M. Taylor: The foreman of W. Young's upper mil. During the Civil War he fought for Co. H, 6th Ind. V.L. and the 2nd Ind. Bat. After sixteen battles, he came to Clinton. He started as an engineer for Young.

Martin White: As an employee of the Young Company, this native Irishman was the foreman of the loading cars. Martin was a city councilman. A Catholic, he was president of the Roman Catholic Total Abstinence Society.

B.C. Brown: A native of NY, he came to Clinton in 1865. In 1872, he became the foreman of Young's lower mill. Brown supposedly patented a splat and shingle mill used in all of Clinton's mill.

Judson Hyde: A native of NY, he was a saw-filer in Young's upper mill. Judson served as the Secretary for the Odd-Fellows lodge. The lodge was on a Harding block in 1874 when Judson was the Secretary. He was also involved with a civic organization called Clinton Encampment, another? Odd Fellows congregation.

George T. McClure: George was the foreman for Lamb's Riverside mill.

John D.C. McClure: Sources differ, but John started as a saw filer in 1869 or 1870 for C. Lamb & Sons. He worked for them until 1883. During that time, he saw the first band saw installed in the Lamb mill. The mill consisted of, or John oversaw, two bands and two gang saws. When John started, "the science of saw filing was in its infancy" either in reference to band saws or all types of saws (B, 67). In 1883, John left for the Lyons Lumber Company where he worked for four years. In 1887, John left for the Southern mills where he became a foreman and a filer at the Woodworth Lumber Company in Bivins, Texas. He later went to Monroe, La to file. John in the late 1890s went to work for the Gates Lumber Company in Wilmar, Arkansas. Through his life, John supposedly filed saws for 55 years. He was called the South's best filer.

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~arbradle/letters/pontius_postcards.html

David W. Switzer: Born in NY in 1833, he came to Clinton in 1857 and started working in the Lamb mills. He eventually became the foreman of the C. Lamb & Son's Stone Mill. According to other notes, Switzer's daughter, Hazel Harriet Gertrude Switzer married William Mowbray Browning in 1902. Hazel was apparently known as Effie?

John Taylor: John worked for the William J. Young & Co as their machinist foreman. Born in NY, John learned his trade in Worcester, MA.

W.M. Taylor: The foreman of W. Young's upper mil. During the Civil War he fought for Co. H, 6th Ind. V.L. and the 2nd Ind. Bat. After sixteen battles, he came to Clinton. He started as an engineer for Young.

Martin White: As an employee of the Young Company, this native Irishman was the foreman of the loading cars. Martin was a city councilman. A Catholic, he was president of the Roman Catholic Total Abstinence Society.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

"My recollections of the Curtis Factory"

"I'm Don Lines, formerly of Fulton, Illinois. Quite a few of us from Fulton worked for the Curtis Factory. You see I'm originally from Fulton, but I live in Forrest Park. The railroad took me to the suburbs of Chicago.

Anyways, I worked for the Curtis Company from 1949 to 1962. I started working in the sash factory on the third floor. I started working for an old German fellow. I think his name was Heine Hake. I kept time for him. He made special order sashes. They were round windows, with half sashes. You could open the top or the bottom half. You could only special order them.

After awhile I was moved to the main office. I scheduled shipments. My boss was Bob Bellis. Mike Grimm, I don't know his first name, scheduled the production. He would decide how much inventory to order. Over in the sales department there was Warren Rosenburg. He ran the sales. There was another gentleman, he was upper management.

In 1962, the Curtis Company didn't have enough work to keep all of us employed. They put us on summer leave. Now I knew the new generation running the factory weren't interested in keeping the company alive. So I got a job with Chicago-Northwestern.

Let's see Curtis opened in 1866 and closed in 1965. The flood of '65 marked the end of Curtis. It was great times."

Recorded August 4th at 2:30 pm by Matt Parbs from Don Lines. Original transcription in folder 2013.6

"My brother was hitchhiking from Mount Vernon, Iowa one day. G.L. Curtis himself picked him up and told him if he ever needed a job to visit him. Well after college my brother went to Curtis to work."

Overhead by docent on August 7th at 4:30pm. Guest left before could be recorded.

Anyways, I worked for the Curtis Company from 1949 to 1962. I started working in the sash factory on the third floor. I started working for an old German fellow. I think his name was Heine Hake. I kept time for him. He made special order sashes. They were round windows, with half sashes. You could open the top or the bottom half. You could only special order them.

After awhile I was moved to the main office. I scheduled shipments. My boss was Bob Bellis. Mike Grimm, I don't know his first name, scheduled the production. He would decide how much inventory to order. Over in the sales department there was Warren Rosenburg. He ran the sales. There was another gentleman, he was upper management.

In 1962, the Curtis Company didn't have enough work to keep all of us employed. They put us on summer leave. Now I knew the new generation running the factory weren't interested in keeping the company alive. So I got a job with Chicago-Northwestern.

Let's see Curtis opened in 1866 and closed in 1965. The flood of '65 marked the end of Curtis. It was great times."

Recorded August 4th at 2:30 pm by Matt Parbs from Don Lines. Original transcription in folder 2013.6

"My brother was hitchhiking from Mount Vernon, Iowa one day. G.L. Curtis himself picked him up and told him if he ever needed a job to visit him. Well after college my brother went to Curtis to work."

Overhead by docent on August 7th at 4:30pm. Guest left before could be recorded.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Role of sawmills & lumber in Immigration and Emigration

Before we begin a thorough look into the pull of the sawmills and forests in migration of the workers, one should start with the men who were providing the pull for the migrants. To do so, I will thoroughly review a 1956 by Frederick Kohlymeyer. In the Journal of Economic History from 1856, an amazing analysis of the lumber elite was found between pages 529 and 538 with the heading Northern Pine Lumberman: A Study in Origins and Migrations. One should not overlook the pull of owning the sawmills and overseeing the lumberjacks. Fred studied 131 preeminent lumbermen, aka lumber owners, and their origin stories. The breakdown shows that 50 of them hailed from the Middle Atlantic, mainly New York, 48 from New England, and 15 from the Midwest. Eighteen of them were from non-American countries, but eight of those were from Canada. The vast majority of them were born from 1810 to 1850 (B, 530).

Seventy-four of these elite hailed from farming families, but one should note that many of the lumberjacks were farmers to make ends meet. Well successful farmers often branched off into other jobs. Surprisingly, 18 of the families engaged in lumbering, and 16 of them engaged in it full time. Some though like Weyerhaeuser or C.A. Smith of Minneapolis were orphans or lost their fathers. 78 of them were only educated through common school. Of note, many taught themselves through the self study of law books and survey manuals (like Abraham Lincoln). Still though 20 percent of the elite were college educated to some degree.

Seemingly the largest push into accession of the elite was the working up of command in the Civil War. From my days at the surveying museum, I noticed that many ranking officers left the service and headed engineer or surveying firms in their home cities. As a result, 74 of the elite were farmers in their youth, 48 had jobs in the lumber industry, 27 were merchants, 22 were military officers, 13 were bookkeepers, 5 were surveyors, 5 were teachers, 11 were professionals, and 10 were carpenters or engaged in construction/ship building.

While a large minority of the lumber elite received help from their families, an amazingly high number (79) of them had their own business by 26. Most of the elite built up enough money to purchase their own mill by saving money earned from other ventures. A large number, 70, created some of the capital from being engaged in a sawmill or forest related occupation.

The answer to overcoming the capital shortage and the new home was to form a partnership. 97 of the elite opened their first mill through a partnership. Many of them took on contract logging. After creating enough capital and gaining a foothold, then they went out on their own. A nugget in the study was the role of fire and migration that spurred on innovations and growth in the sawmills. Because the mills were always on the move and the source of the logs were always on the move, migration was needed, often frequently. As such only 3 of 131 elite made no major change in residence initially. The middle Mississippi was home to 28 elite, and none of them came from the area. 10 of them hailed from Pennsylvania. Even less surprising, rarely did a elite stay put. He usually moved two or three times. Just look at the Joyces and the Weyerhaeusers. Their true home seemed to be Minnesota.

They partnered to create the mills and the supply the demand. All that was needed was a workforce.

Seventy-four of these elite hailed from farming families, but one should note that many of the lumberjacks were farmers to make ends meet. Well successful farmers often branched off into other jobs. Surprisingly, 18 of the families engaged in lumbering, and 16 of them engaged in it full time. Some though like Weyerhaeuser or C.A. Smith of Minneapolis were orphans or lost their fathers. 78 of them were only educated through common school. Of note, many taught themselves through the self study of law books and survey manuals (like Abraham Lincoln). Still though 20 percent of the elite were college educated to some degree.

Seemingly the largest push into accession of the elite was the working up of command in the Civil War. From my days at the surveying museum, I noticed that many ranking officers left the service and headed engineer or surveying firms in their home cities. As a result, 74 of the elite were farmers in their youth, 48 had jobs in the lumber industry, 27 were merchants, 22 were military officers, 13 were bookkeepers, 5 were surveyors, 5 were teachers, 11 were professionals, and 10 were carpenters or engaged in construction/ship building.

While a large minority of the lumber elite received help from their families, an amazingly high number (79) of them had their own business by 26. Most of the elite built up enough money to purchase their own mill by saving money earned from other ventures. A large number, 70, created some of the capital from being engaged in a sawmill or forest related occupation.

The answer to overcoming the capital shortage and the new home was to form a partnership. 97 of the elite opened their first mill through a partnership. Many of them took on contract logging. After creating enough capital and gaining a foothold, then they went out on their own. A nugget in the study was the role of fire and migration that spurred on innovations and growth in the sawmills. Because the mills were always on the move and the source of the logs were always on the move, migration was needed, often frequently. As such only 3 of 131 elite made no major change in residence initially. The middle Mississippi was home to 28 elite, and none of them came from the area. 10 of them hailed from Pennsylvania. Even less surprising, rarely did a elite stay put. He usually moved two or three times. Just look at the Joyces and the Weyerhaeusers. Their true home seemed to be Minnesota.

They partnered to create the mills and the supply the demand. All that was needed was a workforce.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Life in a Literary Sawmill Camp

I just finished a letter of inquiry to the Joyce Foundation about the creation of an exhibit on African-American lumbermen in Jim Crow South. While I knew about the play, Polk County: A Comedy of Negro life on a sawmill camp, with authentic Negro Music, in three acts, I made a wonderful find today on the Library of Congress's website. The play co-authored by Zora Heale Hurston is in its entirety on their website.

What comes about in her tale is an aspect of the American lumber saga that really appeals to me, identity and community. These men, these women, these children, and these families lived in mill towns. The milling defined their employment, but this communal occupation seemed to create a very unique culture and identity of the community. Well, I think. I will admit I haven't done any systematic research, but there are plenty of books on lumberjack culture and lumberjack this. This hides the nuisances of a lumberjack camp. There are a few tales of river pilot culture. These were transient communities in multiple senses. I love the sawmill community and identity because it was often a rooted community.

Last week, a guest recommended Ken Kesey's book, Sometimes a Great Notion. I can't wait to read this book and see about life in a Pacific Northwest lumber camp. All of these stories and all of my research lately seems to be revolving around community, unionization, and identity. It's amazing how lumber creates a truly unique identity, or at least an identity that you can identify as being uniquely lumber. The book is also a movie, Never Give a Inch, featuring Paul Newman and Henry Fonda.

Sawmills and lumber camps also appear in Faulkner books and other literary canons.

Who was the first Mississippi River rafter?

As the story goes, the first man to go down the Mississippi River on a log raft was on the last lumber raft. A beautiful story that necessitates further inquiry.

The first log, well lumber, raft?

From Steamboat Times: In 1839, Henry Merill, Merrill, or Merrell, guided the first documented lumber raft to St Louis by making his raft on the Wisconsin River. According to Source B, the raft, if the same raft, arrived in St. Louis in the spring of 1840. The raft was piloted by a crew of 20 and carried 800,000 lumber feet.

For the St. Louis area, the first lumber raft might have as early as 1831-1832, or 1835 for sure, as rafts from a 300 mile radius would go to St. Louis's mills. E.O. Shepardson, perhaps one of the earliest pilots, helped guide this 100 foot long, 30 foot wide raft to St. Louis (B).

In Source D, there is the story of James Lockwood who navigated a small lumber raft to a local market in 1831 Wisconsin. It is clear from the author that Lockwood's lumber raft was not a success. It arrived in St. Louis greatly reduced. It is also clear that Henry Merill piloted a lumber raft, but Source D shows that due to the existence of certain sawmills, lumber rafts probably went all the way back to 1832.

Key for all of the above is the term lumber raft.

Difference between a log and a lumber raft?

A constant problem for me in research is the difference between a log raft and a lumber raft. I often wonder if the author means to say one or the other. Often there isn't a distinction given.

One of the biggest differences was composition. A lumber raft was much more complex than a log raft, which just consisted of logs strung together. While lumber was strung together, there was the addition of cribs and other stabilizing structures. Also, log rafts were much smaller than lumber rafts, and carried much less board feet. For example, one of the largest lumber rafts had nine million board feet on it while one of the largest log rafts was two million board feet (F, 51).

So what about a log raft?

In source E, Stephen Hanks of Albany, Illinois is credited with being the first person to create a log raft. Up until 1844, only lumber rafts existed on the Mississippi. Like many farmers, Stephen found himself in a lumber camp in the winter of 1844. He had driven his cattle to the camp and found himself faced with an opportunity. Up to this point, the logs were driven by current, but in the spring of 1844, Hanks tied the logs together and drove it to St. Louis (E, 162). A flawed primary source, gives Hanks inspiration of a large log raft to go from Wisconsin to St. Louis to his family who made small log rafts around their local sawmill in 1837 to 1838 (G, 81).

How long did a log/lumber raft take?

From Source B, the rafts could take up to two months to go from Wisconsin to St. Louis until the introduction of steamboats, which cut the time down to two weeks. The season according to Source B starts May and ends November 15. Of course, everything needs an exception, so once a raft went from La Crosse to New Orleans in 1870. It took ten weeks.

Introduction of steam?

Source B credits Schudenburg & Boeckeler Timber Company as the company that produced the device needed to steer millions of board feet. The "Mollie Whetmore" was the first steamer. Then again, Source E talks about J.W. Van Sant from Le Claire, Iowa who produced the "stern-wheeler" to push the logs down the river in 1870. The man responsible for this could said to be Weyerhaeuser. He didn't invent it, but his mill was on the receiving end of the raft.

A question I have is what took so long, as the first steamboat to ride the upper Mississippi River was the Virginia in 1823. In 1829, the steamboat, Heliopolis, became the first successful snagboat as it opened up the snags in the river (C, 24). Then even though steam existed, when the log rafts hit patches of no current, the rafters would kedge the raft down the river. A small boat would get in front of the raft, drop anchor, and then the rafters would "somehow" as the author didn't really say, pull the raft to the anchor. I envision hooking the chain E, 162).

Source E highlights why LeClaire became a center for rafting because of the rapids. Le Claire had up to sixteen rapid pilots working from 1840 to 1915 (E, 162).

Why rafts?

According to Source B, the steamboats, having a crew of 18, could bring up to 3.5 million board feet worth of logs down the river. It would take seven trains of fifty cars each to do the same. The cost to employ a raftman was usually $1.50 to $3.00 a day (D).

The supposed last raft?

July 1, 1915, the Ottumwa Belle came to its final resting spot in Fort Madison, Iowa. On its trip down the river, it stopped in Albany to pick up a 93 year old Stephen Hanks to go as far as Davenport. Hanks therefore was the first and last rafter (E, 168). It should be noted I've read this as both a log and a lumber raft. I tend to give the credit to the Grand Excursions book that says Hanks took the first log raft and the last lumber raft. This also comes up in book, The Immortal River. Hanks also was one of the first to ride a lumber raft down the river, the first log rafter, and practically the last lumber rafter. This of course begs the question of when was the last log raft!!!!!

Why is this all important?

Because before 1844, the sawmills that sent pine South were all up in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Hanks allowed for Clinton sawmills and Weyerhaeuser's sawmills to thrive. After the introduction of steam, a raft could carry enough lumber to build 125 houses. Typically or apparently, 800 lumber rafts would go down the river each year between the 1892 and 1900 (E, 125). Therefore, every year 100,000 homes floated down the river.

It leads to a future post on the Mississippi River Logging Company, which is in my nascent opinion the single most important thing to propel Clinton to the Lumber Capital of the World... well railroads will have an argument.

Sources:

A. http://steamboattimes.com/rafts.html

B. http://books.google.com/books?id=mXUCAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA4-PR10&lpg=RA4-PR10&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=ks1Ky8Knp6&sig=QLSJf2h1ihHRPKW8uRCx4oOLZBE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CGgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=timber%20raft%20mississippi%20river&f=false

C. http://books.google.com/books?id=iqH1gzJezPQC&pg=PA103&lpg=PA103&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=1zuXcK7N-p&sig=z-7b0nq3Ob4nQ5RmTk_9JU28D5c&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CGoQ6AEwCg#v=onepage&q=first&f=false

D. http://www.mcmillanlibrary.org/rosholt/wi-logging-book/wilogging/images/00000027.pdf

E. http://books.google.com/books?id=ro6Fsh9m5gsC&pg=PA124&lpg=PA124&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=nJRID-lN2b&sig=IdBOm4mNNDV34kC7HPzyCcqCsHg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CG0Q6AEwCw#v=onepage&q=Hanks&f=false

F. http://books.google.com/books?id=PYAu8pLDzWEC&pg=PA54&lpg=PA54&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=rZaX0jMrNx&sig=JTwYiwYn0i8vI5jjX6hoZh4GLps&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CG8Q6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=raft&f=false

G. http://books.google.com/books?id=XEJk4r0wIjYC&pg=PA353&dq=last+raft+on+the+Mississippi+River&hl=en&sa=X&ei=D0vnUbvEDsG9qwHv-IGQBA&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Hanks&f=false

The first log, well lumber, raft?

From Steamboat Times: In 1839, Henry Merill, Merrill, or Merrell, guided the first documented lumber raft to St Louis by making his raft on the Wisconsin River. According to Source B, the raft, if the same raft, arrived in St. Louis in the spring of 1840. The raft was piloted by a crew of 20 and carried 800,000 lumber feet.

For the St. Louis area, the first lumber raft might have as early as 1831-1832, or 1835 for sure, as rafts from a 300 mile radius would go to St. Louis's mills. E.O. Shepardson, perhaps one of the earliest pilots, helped guide this 100 foot long, 30 foot wide raft to St. Louis (B).

In Source D, there is the story of James Lockwood who navigated a small lumber raft to a local market in 1831 Wisconsin. It is clear from the author that Lockwood's lumber raft was not a success. It arrived in St. Louis greatly reduced. It is also clear that Henry Merill piloted a lumber raft, but Source D shows that due to the existence of certain sawmills, lumber rafts probably went all the way back to 1832.

Key for all of the above is the term lumber raft.

Difference between a log and a lumber raft?

A constant problem for me in research is the difference between a log raft and a lumber raft. I often wonder if the author means to say one or the other. Often there isn't a distinction given.

One of the biggest differences was composition. A lumber raft was much more complex than a log raft, which just consisted of logs strung together. While lumber was strung together, there was the addition of cribs and other stabilizing structures. Also, log rafts were much smaller than lumber rafts, and carried much less board feet. For example, one of the largest lumber rafts had nine million board feet on it while one of the largest log rafts was two million board feet (F, 51).

So what about a log raft?

In source E, Stephen Hanks of Albany, Illinois is credited with being the first person to create a log raft. Up until 1844, only lumber rafts existed on the Mississippi. Like many farmers, Stephen found himself in a lumber camp in the winter of 1844. He had driven his cattle to the camp and found himself faced with an opportunity. Up to this point, the logs were driven by current, but in the spring of 1844, Hanks tied the logs together and drove it to St. Louis (E, 162). A flawed primary source, gives Hanks inspiration of a large log raft to go from Wisconsin to St. Louis to his family who made small log rafts around their local sawmill in 1837 to 1838 (G, 81).

How long did a log/lumber raft take?

From Source B, the rafts could take up to two months to go from Wisconsin to St. Louis until the introduction of steamboats, which cut the time down to two weeks. The season according to Source B starts May and ends November 15. Of course, everything needs an exception, so once a raft went from La Crosse to New Orleans in 1870. It took ten weeks.

Introduction of steam?

Source B credits Schudenburg & Boeckeler Timber Company as the company that produced the device needed to steer millions of board feet. The "Mollie Whetmore" was the first steamer. Then again, Source E talks about J.W. Van Sant from Le Claire, Iowa who produced the "stern-wheeler" to push the logs down the river in 1870. The man responsible for this could said to be Weyerhaeuser. He didn't invent it, but his mill was on the receiving end of the raft.

A question I have is what took so long, as the first steamboat to ride the upper Mississippi River was the Virginia in 1823. In 1829, the steamboat, Heliopolis, became the first successful snagboat as it opened up the snags in the river (C, 24). Then even though steam existed, when the log rafts hit patches of no current, the rafters would kedge the raft down the river. A small boat would get in front of the raft, drop anchor, and then the rafters would "somehow" as the author didn't really say, pull the raft to the anchor. I envision hooking the chain E, 162).

Source E highlights why LeClaire became a center for rafting because of the rapids. Le Claire had up to sixteen rapid pilots working from 1840 to 1915 (E, 162).

Why rafts?

According to Source B, the steamboats, having a crew of 18, could bring up to 3.5 million board feet worth of logs down the river. It would take seven trains of fifty cars each to do the same. The cost to employ a raftman was usually $1.50 to $3.00 a day (D).

The supposed last raft?

July 1, 1915, the Ottumwa Belle came to its final resting spot in Fort Madison, Iowa. On its trip down the river, it stopped in Albany to pick up a 93 year old Stephen Hanks to go as far as Davenport. Hanks therefore was the first and last rafter (E, 168). It should be noted I've read this as both a log and a lumber raft. I tend to give the credit to the Grand Excursions book that says Hanks took the first log raft and the last lumber raft. This also comes up in book, The Immortal River. Hanks also was one of the first to ride a lumber raft down the river, the first log rafter, and practically the last lumber rafter. This of course begs the question of when was the last log raft!!!!!

Why is this all important?

Because before 1844, the sawmills that sent pine South were all up in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Hanks allowed for Clinton sawmills and Weyerhaeuser's sawmills to thrive. After the introduction of steam, a raft could carry enough lumber to build 125 houses. Typically or apparently, 800 lumber rafts would go down the river each year between the 1892 and 1900 (E, 125). Therefore, every year 100,000 homes floated down the river.

It leads to a future post on the Mississippi River Logging Company, which is in my nascent opinion the single most important thing to propel Clinton to the Lumber Capital of the World... well railroads will have an argument.

Sources:

A. http://steamboattimes.com/rafts.html

B. http://books.google.com/books?id=mXUCAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA4-PR10&lpg=RA4-PR10&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=ks1Ky8Knp6&sig=QLSJf2h1ihHRPKW8uRCx4oOLZBE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CGgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=timber%20raft%20mississippi%20river&f=false

C. http://books.google.com/books?id=iqH1gzJezPQC&pg=PA103&lpg=PA103&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=1zuXcK7N-p&sig=z-7b0nq3Ob4nQ5RmTk_9JU28D5c&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CGoQ6AEwCg#v=onepage&q=first&f=false

D. http://www.mcmillanlibrary.org/rosholt/wi-logging-book/wilogging/images/00000027.pdf

E. http://books.google.com/books?id=ro6Fsh9m5gsC&pg=PA124&lpg=PA124&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=nJRID-lN2b&sig=IdBOm4mNNDV34kC7HPzyCcqCsHg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CG0Q6AEwCw#v=onepage&q=Hanks&f=false

F. http://books.google.com/books?id=PYAu8pLDzWEC&pg=PA54&lpg=PA54&dq=timber+raft+mississippi+river&source=bl&ots=rZaX0jMrNx&sig=JTwYiwYn0i8vI5jjX6hoZh4GLps&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RjznUeH2EO2yygGj7YCQBg&ved=0CG8Q6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=raft&f=false

G. http://books.google.com/books?id=XEJk4r0wIjYC&pg=PA353&dq=last+raft+on+the+Mississippi+River&hl=en&sa=X&ei=D0vnUbvEDsG9qwHv-IGQBA&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Hanks&f=false

Saturday, June 22, 2013

A Trip Along the Book Racks... Naturally Made Out of Wood

One of my favorite past times is watching a movie and reading book titles and their synopses. To each his own. I love weaving stories with them and imagining what is inside the covers.

Once up a lumber town, a book by Roselynn Ederer, tells the story of Saginaw, a Michigan lumber town. Apparently its book three of a three book series. A Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho and the Potlatch Lumber Company, showed how the frontier was settled and big business exploited the natural resources of the frontier. There, people like Edward Rada could be found Singing My Song: Growing Up in a Lumber Town: Mill City, Oregon 1916-1939.

At this time, the Lumber Kings and Shantymen: Logging and Lumbering in the Ottawa Valley, by David Lee, the lumber industry was going through another change. Towns like Ottawa were becoming "government towns" instead of lumber towns by the 1920s. Books like David Lee's make sure to show a social history combined with an economic history, well he says cultural, to tell the story of a Canadian legacy.

Once up a lumber town, a book by Roselynn Ederer, tells the story of Saginaw, a Michigan lumber town. Apparently its book three of a three book series. A Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho and the Potlatch Lumber Company, showed how the frontier was settled and big business exploited the natural resources of the frontier. There, people like Edward Rada could be found Singing My Song: Growing Up in a Lumber Town: Mill City, Oregon 1916-1939.

At this time, the Lumber Kings and Shantymen: Logging and Lumbering in the Ottawa Valley, by David Lee, the lumber industry was going through another change. Towns like Ottawa were becoming "government towns" instead of lumber towns by the 1920s. Books like David Lee's make sure to show a social history combined with an economic history, well he says cultural, to tell the story of a Canadian legacy.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

I hail from Lumberton...

Lumbertons abound all over the map. One would think these towns were lumber centers, as towns are usually either named after people or the physical characteristics surrounding the town. The most prevalent and perhaps oldest Lumberton is Lumberton, North Carolina, the town that claimed the life of Michael Jordan's father. I say the town because some studies show it might be the environment and demographics in Lumberton that cause such violence. The town was also the fictional setting for David Lynch's rather disturbing but yet amazing movie, Blue Velvet. The real town sits in the home of the Lumbees, a Native American tribe, and it rests on the Lumber River in Robeson County, North Carolina. Yet, how did it get its name, and what about other Lumbertons?

The of Lumberton, North Carolina received its name in 1787 from General John Willis, a resident of the area and oh by the way, a Revolutionary hero. The river it sits on, Lumber River, originally was named Drowning Creek. According to Wikipedia, it was in 1809 that the name was changed to Lumber River to recognize the lumber industry. The citation can also be found in Robeson County by K. Blake Tyner. So when you read that the town got its name for being on the Lumber River, what gives?

What gives is the age of these industries. The Lumbee River, the Drowning River, or the Lumber River all made Lumberton a vital point in the log drives down the river in the late 1700s. Lumberton for a time developed a heavy timber industry. When the industry shifted, the structures disappeared. Cotton became king.

Yet, Lumbertons abound. Jim Brown, in his book Foot Prints, talks about life in Lumberton, Mississippi. He talks about how Lumberton received its name during the very beginning of the South's lumber boom. The industry boomed in the early 1900s -- note when Clinton's reign ended. Lumberton was one of many sawmill towns in Mississippi like Picayune, Sumrall, Wiggins, and Laurel.

|

| Screen Shot of Lumberton in David Lynch's Blue Velvet |

The of Lumberton, North Carolina received its name in 1787 from General John Willis, a resident of the area and oh by the way, a Revolutionary hero. The river it sits on, Lumber River, originally was named Drowning Creek. According to Wikipedia, it was in 1809 that the name was changed to Lumber River to recognize the lumber industry. The citation can also be found in Robeson County by K. Blake Tyner. So when you read that the town got its name for being on the Lumber River, what gives?

What gives is the age of these industries. The Lumbee River, the Drowning River, or the Lumber River all made Lumberton a vital point in the log drives down the river in the late 1700s. Lumberton for a time developed a heavy timber industry. When the industry shifted, the structures disappeared. Cotton became king.

Yet, Lumbertons abound. Jim Brown, in his book Foot Prints, talks about life in Lumberton, Mississippi. He talks about how Lumberton received its name during the very beginning of the South's lumber boom. The industry boomed in the early 1900s -- note when Clinton's reign ended. Lumberton was one of many sawmill towns in Mississippi like Picayune, Sumrall, Wiggins, and Laurel.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Where was the richest town in America?

A common phrase used to describe Clinton during the lumber boom was that Clinton was the richest town in America. The statement is quantifiably qualified by saying it had more millionaires per capita than any other town in America, sometimes an additional qualifier is added of a town west of the Mississippi. I naturally needed to find out if this was true. I knew that this phrase, the richest town, could be more figurative than literal, but what I discovered in researching the richest town in America showed the true meaning of the phrase.

The first qualifier should be time. I chose to look at the time period of 1870 to 1900 to see where the richest town in America was. For example, Lynchburg, Virginia likes to say it was the richest town in America along with New Bedford, MA in the 1850's. By 1910, Valdosta, Georgia references a Forbes article that said they were the richest town per capita in America.

Another qualifier needs to be millionaires and not richest. Clinton might have had as many as 17 millionaires, but that doesn't mean it was the richest town. The economic studies are startling in how much more money the north had per capita than the South, but representative of America at a whole, this doesn't mean that there wasn't a small group of uber wealthy families.

So the quest began, and what an amazing insight into the American economy and remembrance manifested itself. Right away I was introduced to Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania. During our time period, the town was home to perhaps 13 millionaires. The town's history though credits "that over a dozen towns and cities claim they had the most millionaires per capita of any city in the United States." The wonderful article lists thirteen towns that make the claim, and doesn't even include Clinton. A Forbes article (E) claims that more than 20 towns made the same claim for the same time period.

The first qualifier should be time. I chose to look at the time period of 1870 to 1900 to see where the richest town in America was. For example, Lynchburg, Virginia likes to say it was the richest town in America along with New Bedford, MA in the 1850's. By 1910, Valdosta, Georgia references a Forbes article that said they were the richest town per capita in America.

Another qualifier needs to be millionaires and not richest. Clinton might have had as many as 17 millionaires, but that doesn't mean it was the richest town. The economic studies are startling in how much more money the north had per capita than the South, but representative of America at a whole, this doesn't mean that there wasn't a small group of uber wealthy families.

So the quest began, and what an amazing insight into the American economy and remembrance manifested itself. Right away I was introduced to Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania. During our time period, the town was home to perhaps 13 millionaires. The town's history though credits "that over a dozen towns and cities claim they had the most millionaires per capita of any city in the United States." The wonderful article lists thirteen towns that make the claim, and doesn't even include Clinton. A Forbes article (E) claims that more than 20 towns made the same claim for the same time period.

Friday, May 24, 2013

Sawmill Encyclopedia

A frustration of mine is trying to remember all the people, all the firsts, all the terms, all the legislation, all the events of a subject. The joy of my job is I'm charged with making sense of all these "facts" and turning them into stories.

I find that a continually updated encyclopedia of knowledge works the best. Bookmark this post, as this post will never be finished. Please feel free to add suggestions/entries below in the comments. Include your sources if you can. No factoid is too obscure or small to be included. If you want to add to any existing entry or correct any entry, please leave a comment. If anyone wants to help write for the blog or this entry, I can give you the power of the pen. While our museum focuses on Clinton, the entire history of sawmills and the lumber industry fits this encyclopedia. The hope is that the next time someone says, "Well when was the first sawmill fire in Clinton?" I can say well I think it is this, but let me check my encyclopedia....

Entries:

A note on citation. As I'm finding new sources all the time, instead of offering Author and details, the sources will be organized off letter and corresponding page number/placement.

People:

Batchelder, D.J.:

Dulany, George W.: Born in Hannibal, Missouri in 1855, George would go on to establish the Eclipse Lumber Company.

John Ericsson, Inventor: At the age of ten, John, born in Sweden on July 31, 1803, designed and built a miniature sawmill. (B, 16) Why is he famous? He, along with his brother and others, designed and built the Monitor, the ironclad used by the US during the Civil War.

Gardiner, Silas: Silas served in the General Assembly of Iowa from 1892 to 1894, but he got his start as one of the pioneering lumbermen of Lyons. His father's friend was Chancy Lamb, and it was with the Lambs that Silas got his start. Eventually Sials bought in with the Lambs in the company Lamb, Byng Lumber. In 1877, this company became C. Lamb & Sons. Silas had a home both in Clinton and Laurel, Mississippi. Jumping from a train in 1878 caused him to lose his legs.

Haun, William G. : Operated Union Grist Mill which opened in 1856. The mill was located on the river about 8 blocks from The Sawmill Museum.

Logsdon, Laurence: Laurence moved to Clinton in 1880 and he worked as an edger in the mills for three years.

Smith, George C.: An English immigrant, George went from farming with this father in Elvira, Iowa to working in the mills to being an original founder and eventual president of Clinton Paper Company. He got his start in the mills as an engineer at the newly started up Clinton Lumber Company. He also worked for the Lamb & Sons mill.

Stumbaugh, G.H.: With partner Samuel Cox built the first sawmill in Lyons in 1855. The mill was purcahsed by Ira Stockwell in 1859.

Thorn, George: Mirroring many frontier communities, George Thorn built the town of Toronto, Iowa through the construction of a sawmill in 1844, a grist mill two years later, and then economic centers like a store. The mill, Wolfe's History of CC doesn't define which, was sold multiple times until its eventual destruction by fire on April 19, 1909. It's longest owner was David O. Kidd. An amazing set of documents on George Thorn: https://www.legis.iowa.gov/DOCS/LSA/History_Docs/11th%20GA/Thorne,%20George%20W.pdf

Wadleigh, L.B.:

Welles, E.P.:

Wisner, Frank: Son of Frank George Wisner, a lumberman born in Clinton, and Mary Jeanette Gardiner, of Clinton. Frank Wisner was an early head figure in the CIA and the OSS.

Tools:

Hand Spike: Early river drive tool to cant and lift logs. It was a five foot pole with a spike (A, 124).

Peavey: The tool is named after Joseph Peavey, a Maine resident and forger, who place a spike on a five-foot ironwood stock, like a handspike, but added the "pointed, thumb-like hook to move up and down, but not, like the swing dog, sideways (A,24)."

Pike Pole: Like a peavey, but usually longer at 12 feet, made of spruce or ash. It had a "blunt toe or a gaff similar to a boat hook (A, 124)."

Laws:

Log Cabin Law/ Preemeption Act of 1841: Legalized squatting rights. If a head of the family (certain definitions) had built a cabin on some land and paid the price of $1.25 per acre, then that head could obtain rights to up to 160 acres. (D/E)

Timber Culture Act of 1873: This law created an avenue for settlers to claim 160 acres of land by converting 40 acres of the land into timber. Aimed at the arid West and aimed at novice settlers, this law failed. The failure happened even after a reduction of the required acres for timber to ten acres.

Free Timber Act of 1878: If land had been reserved for mineral use, citizens could cut timber for their personal building needs. (D/E)

Timber and Stone Act of 1878: Allowed for individuals to purchase 160 acres of timber and mineral rich land from the government. Both acts of 1878 were exploited by lumber companies, as the "individuals" were agents of the lumber/timber companies. (D/E)

Companies:

Eastman, Gardiner, & Company: In 1891, the Lyons firm purchased a sawmill in downtown Laurel, Mississippi. The company operated until 1937 supposedly in Mississippi.

Eclipse Lumber Company: Originally established in Minneapolis in 1894, the firm moved to Clinton in 1910. By 1944, the company, based in Clinton, Iowa. had over 36 outlets. One feature of the company was the incorporation of home planning offices in their lumber yards.

Harrison, Ward, & Company

Itasca Company: Company founded by the W.T. Joyce and H.C. Ackeley in 1887. Invested together in the creation of the Itasca rail.Company based in Minnesota.

Joyce Lumber Company: Headquarters and branch office was located in Clinton. The company's legacy is now represented through the Joyce Foundation.

United Lumber Company

Wadleigh, Welles, and Co

Welles, Gardiner, & Co:

Events:

Terms:

Silviculture: The treatment of trees/forests as crops or really the growing and cultivation of trees.

Logging Boats & The River

Clinton Lumber Barons Other Businesses:

City National Bank: Bank was a partnership between the Lambs, Wadleighs, Curtises, Carpenters (relatives of Curtis), and others.

Clinton National Bank: Chartered in 1865, eventually the Youngs took ownership of the bank

Clinton Savings Bank: The Lambs and Youngs had interests in this bank

Sources:

A. http://books.google.com/books?id=tWosMqKAv1oC&pg=PA124&dq=pike+pole+peavey&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_ZGfUY-hCab7yAGZ2YGoDw&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=pike%20pole%20peavey&f=false

B. http://books.google.com/books?id=NmODrlEknzoC&pg=PA16&dq=miniature+sawmill+display&hl=en&sa=X&ei=W5GfUcDhEoOTyQG5lYGADw&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=miniature%20sawmill%20display&f=false

C. http://books.google.com/books?id=odgOl06HasQC&pg=PA66&dq=christopher+columbus+sawmill&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vrS3UcDGLOz_4AO5wYDwBw&ved=0CEcQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=christopher%20columbus%20sawmill&f=false

D. http://books.google.com/books?id=dZYGdbWTXesC&pg=PA138&dq=homestead+act+logging&hl=en&sa=X&ei=s2j-UezRC5KByQH2l4HIBA&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=homestead%20act%20logging&f=false

E. http://books.google.com/books?id=bcdo0qlS0awC&pg=PA124&dq=%22log+cabin+law%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=E2z-UdybL6WOyAH8hoGQDA&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22log%20cabin%20law%22&f=false

F. http://www.msrailroads.com/EG&Co.htm

I find that a continually updated encyclopedia of knowledge works the best. Bookmark this post, as this post will never be finished. Please feel free to add suggestions/entries below in the comments. Include your sources if you can. No factoid is too obscure or small to be included. If you want to add to any existing entry or correct any entry, please leave a comment. If anyone wants to help write for the blog or this entry, I can give you the power of the pen. While our museum focuses on Clinton, the entire history of sawmills and the lumber industry fits this encyclopedia. The hope is that the next time someone says, "Well when was the first sawmill fire in Clinton?" I can say well I think it is this, but let me check my encyclopedia....

Entries:

A note on citation. As I'm finding new sources all the time, instead of offering Author and details, the sources will be organized off letter and corresponding page number/placement.

People:

Batchelder, D.J.:

Dulany, George W.: Born in Hannibal, Missouri in 1855, George would go on to establish the Eclipse Lumber Company.

John Ericsson, Inventor: At the age of ten, John, born in Sweden on July 31, 1803, designed and built a miniature sawmill. (B, 16) Why is he famous? He, along with his brother and others, designed and built the Monitor, the ironclad used by the US during the Civil War.

Gardiner, Silas: Silas served in the General Assembly of Iowa from 1892 to 1894, but he got his start as one of the pioneering lumbermen of Lyons. His father's friend was Chancy Lamb, and it was with the Lambs that Silas got his start. Eventually Sials bought in with the Lambs in the company Lamb, Byng Lumber. In 1877, this company became C. Lamb & Sons. Silas had a home both in Clinton and Laurel, Mississippi. Jumping from a train in 1878 caused him to lose his legs.

Haun, William G. : Operated Union Grist Mill which opened in 1856. The mill was located on the river about 8 blocks from The Sawmill Museum.

Logsdon, Laurence: Laurence moved to Clinton in 1880 and he worked as an edger in the mills for three years.

Smith, George C.: An English immigrant, George went from farming with this father in Elvira, Iowa to working in the mills to being an original founder and eventual president of Clinton Paper Company. He got his start in the mills as an engineer at the newly started up Clinton Lumber Company. He also worked for the Lamb & Sons mill.

Stumbaugh, G.H.: With partner Samuel Cox built the first sawmill in Lyons in 1855. The mill was purcahsed by Ira Stockwell in 1859.

Thorn, George: Mirroring many frontier communities, George Thorn built the town of Toronto, Iowa through the construction of a sawmill in 1844, a grist mill two years later, and then economic centers like a store. The mill, Wolfe's History of CC doesn't define which, was sold multiple times until its eventual destruction by fire on April 19, 1909. It's longest owner was David O. Kidd. An amazing set of documents on George Thorn: https://www.legis.iowa.gov/DOCS/LSA/History_Docs/11th%20GA/Thorne,%20George%20W.pdf

Wadleigh, L.B.:

Welles, E.P.:

Wisner, Frank: Son of Frank George Wisner, a lumberman born in Clinton, and Mary Jeanette Gardiner, of Clinton. Frank Wisner was an early head figure in the CIA and the OSS.

Tools:

Hand Spike: Early river drive tool to cant and lift logs. It was a five foot pole with a spike (A, 124).

Peavey: The tool is named after Joseph Peavey, a Maine resident and forger, who place a spike on a five-foot ironwood stock, like a handspike, but added the "pointed, thumb-like hook to move up and down, but not, like the swing dog, sideways (A,24)."

Pike Pole: Like a peavey, but usually longer at 12 feet, made of spruce or ash. It had a "blunt toe or a gaff similar to a boat hook (A, 124)."

Laws:

Log Cabin Law/ Preemeption Act of 1841: Legalized squatting rights. If a head of the family (certain definitions) had built a cabin on some land and paid the price of $1.25 per acre, then that head could obtain rights to up to 160 acres. (D/E)

Timber Culture Act of 1873: This law created an avenue for settlers to claim 160 acres of land by converting 40 acres of the land into timber. Aimed at the arid West and aimed at novice settlers, this law failed. The failure happened even after a reduction of the required acres for timber to ten acres.

Free Timber Act of 1878: If land had been reserved for mineral use, citizens could cut timber for their personal building needs. (D/E)

Timber and Stone Act of 1878: Allowed for individuals to purchase 160 acres of timber and mineral rich land from the government. Both acts of 1878 were exploited by lumber companies, as the "individuals" were agents of the lumber/timber companies. (D/E)

Companies:

Eastman, Gardiner, & Company: In 1891, the Lyons firm purchased a sawmill in downtown Laurel, Mississippi. The company operated until 1937 supposedly in Mississippi.

Eclipse Lumber Company: Originally established in Minneapolis in 1894, the firm moved to Clinton in 1910. By 1944, the company, based in Clinton, Iowa. had over 36 outlets. One feature of the company was the incorporation of home planning offices in their lumber yards.

Harrison, Ward, & Company

Itasca Company: Company founded by the W.T. Joyce and H.C. Ackeley in 1887. Invested together in the creation of the Itasca rail.Company based in Minnesota.

Joyce Lumber Company: Headquarters and branch office was located in Clinton. The company's legacy is now represented through the Joyce Foundation.

United Lumber Company

Wadleigh, Welles, and Co

Welles, Gardiner, & Co:

Events:

Terms:

Silviculture: The treatment of trees/forests as crops or really the growing and cultivation of trees.

Logging Boats & The River

Clinton Lumber Barons Other Businesses:

City National Bank: Bank was a partnership between the Lambs, Wadleighs, Curtises, Carpenters (relatives of Curtis), and others.

Clinton National Bank: Chartered in 1865, eventually the Youngs took ownership of the bank

Clinton Savings Bank: The Lambs and Youngs had interests in this bank

Sources:

A. http://books.google.com/books?id=tWosMqKAv1oC&pg=PA124&dq=pike+pole+peavey&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_ZGfUY-hCab7yAGZ2YGoDw&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=pike%20pole%20peavey&f=false

B. http://books.google.com/books?id=NmODrlEknzoC&pg=PA16&dq=miniature+sawmill+display&hl=en&sa=X&ei=W5GfUcDhEoOTyQG5lYGADw&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=miniature%20sawmill%20display&f=false

C. http://books.google.com/books?id=odgOl06HasQC&pg=PA66&dq=christopher+columbus+sawmill&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vrS3UcDGLOz_4AO5wYDwBw&ved=0CEcQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=christopher%20columbus%20sawmill&f=false

D. http://books.google.com/books?id=dZYGdbWTXesC&pg=PA138&dq=homestead+act+logging&hl=en&sa=X&ei=s2j-UezRC5KByQH2l4HIBA&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=homestead%20act%20logging&f=false

E. http://books.google.com/books?id=bcdo0qlS0awC&pg=PA124&dq=%22log+cabin+law%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=E2z-UdybL6WOyAH8hoGQDA&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22log%20cabin%20law%22&f=false

F. http://www.msrailroads.com/EG&Co.htm

Friday, May 17, 2013

Roots of Logrolling & Lumberjack Festival

"A lumberjack will hold the log until you and your partner are on top of it. When the two of you are ready, the lumberjack simply lets go of the log. Now the game is on to see who can stay up the longest. After you fall in, hop back in line and do it again!" This exists only at our Third Annual Lumberjack Camp, held on July 13, on the grounds of The Sawmill Museum.

The Festival is our big event held the second Saturday of July annually that features 30-40 lumberjacks competing in multiple different events. We hope the log rolling demos and chances for fans attempting to stay on top of the log will be "a big occasion, and in the way of good cheer and a spontaneous flow of friendship and neighborly love (History of Jackson County, Georgia)."

With the lumber industry of the late 1800s focused on the Northwoods, the men and women living in the woods of Georgia would meet every year to "logroll" and have a big party. Oddly this logrolling was actually log-piling for a big bonfire. The people just called it logrolling and there were various branded "logrolls." The whole community would come out, have crafts (like we will have on July 13), a big dance at night (the Jaycee's will have a Street Festival), and a community building event.

Our notion of logrolling starts in the late 1800s, but with the word birler. The roots of logrolling come from a change of transportation in the mid-1800s. Replacing and/or challenging log rafts, log drives transported more logs at a quicker rate down the river. The art of log drive required a lumberjack to jump from one log to another as the logs made its way down the river to a log boom near a sawmill. As the logs bobbed and bounced in the fast current, men had to keep their balance. Logrolling was born out of survival.

The Festival is our big event held the second Saturday of July annually that features 30-40 lumberjacks competing in multiple different events. We hope the log rolling demos and chances for fans attempting to stay on top of the log will be "a big occasion, and in the way of good cheer and a spontaneous flow of friendship and neighborly love (History of Jackson County, Georgia)."

With the lumber industry of the late 1800s focused on the Northwoods, the men and women living in the woods of Georgia would meet every year to "logroll" and have a big party. Oddly this logrolling was actually log-piling for a big bonfire. The people just called it logrolling and there were various branded "logrolls." The whole community would come out, have crafts (like we will have on July 13), a big dance at night (the Jaycee's will have a Street Festival), and a community building event.

Our notion of logrolling starts in the late 1800s, but with the word birler. The roots of logrolling come from a change of transportation in the mid-1800s. Replacing and/or challenging log rafts, log drives transported more logs at a quicker rate down the river. The art of log drive required a lumberjack to jump from one log to another as the logs made its way down the river to a log boom near a sawmill. As the logs bobbed and bounced in the fast current, men had to keep their balance. Logrolling was born out of survival.

Saturday, May 4, 2013

Abraham Lincoln & The New Salem Sawmill

Sadly not everything is recorded in history. There is no pay stub showing that Abraham Lincoln worked at New Salem's sawmill. Funny though, he did work in a sawmill -- well the grist mill side of Denton Offutt's mill. In 1831, Offutt gave Lincoln his first job in New Salem. At the mill, Lincoln's work ethic and his dealing with farmer's wheat caught the eye of visitors and townspeople alike.

Sadly, no one talked about Abe working in the sawmill. What's important for us though is Lincoln found himself working at the heart of "every" frontier community. New Salem's founders owned the grist & sawmill, and it served as the economic magnet for New Salem. While not necessarily the first business in a town, the appearance of a mill in a town drove commerce. It brought surrounding farmers to town, and to capitalize on the farmer's waiting for their lumber of milled crops, businesses popped up to take their money. Surveyors and town planners used the presence of a mill to drive sales and prices.

In July 1831, Abe found himself working at this center. The truth is that while some saw him work the mill, Lincoln mainly worked Offutt's store. Abe's boyhood life illustrated why it was so important for a town to have a dual mill in the heart of town operated by water or animals. As a boy, he went with his father over seven miles to a hand-grind mill. Here he fell in love with the machinery of the mills, and supposedly could watch the mills for hours (Burlingame).

|

| Working model sawmill housed at New Salem |

In July 1831, Abe found himself working at this center. The truth is that while some saw him work the mill, Lincoln mainly worked Offutt's store. Abe's boyhood life illustrated why it was so important for a town to have a dual mill in the heart of town operated by water or animals. As a boy, he went with his father over seven miles to a hand-grind mill. Here he fell in love with the machinery of the mills, and supposedly could watch the mills for hours (Burlingame).

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

My First Sawing

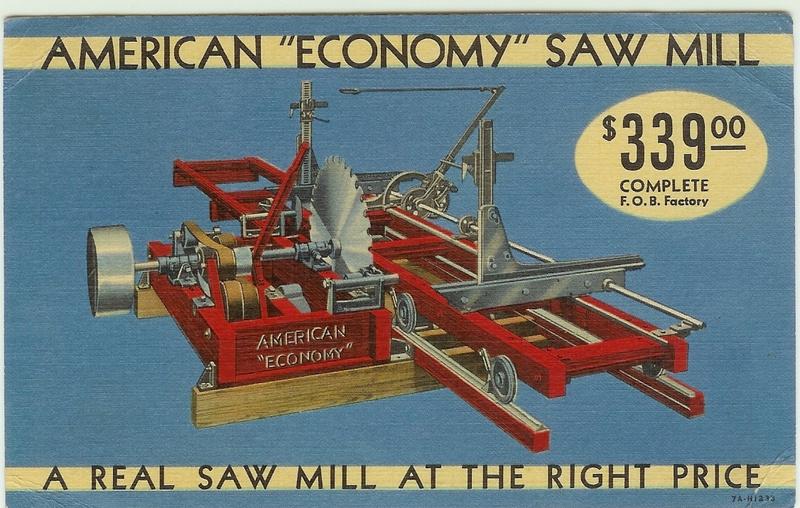

Last Sunday, the 7th, the sawyers trusted me to be the clutch man. At least one Sunday a month, the museum fires up the saw to offer live demonstrations of a running sawmill. Our saw is a circa 1923-1928 American No. 1 Variable Belt Feed Saw Mill called the "best Small Saw Mill made for use with Farm tractors and other similar power." Two can run it dangerously, three can run it with caution, four you can breathe, and five or six makes life easy. We had five on Sunday.

At least I didn't use half numbers, as did The American Sawmill Machinery Company to name the sawmills that hailed from the Hackettstown, New Jersey factory. The company had a wide list of sawmills, one named Heavy Duty 7 1/2, but my favorite little ordering fact was that they made left handed sawmills on request. Our mill can cut logs up to 24 inches in diameter. We can cut larger logs, but it takes a constant rotation of the log to cut. The American Company is a familiar name to amateur and professional sawyers.

Anyways, I ran the engine, a Caterpillar diesel from the 1950s. I would engage the clutch to get the mill running and disengage the clutch to kill it. To engage, you have to push a large black rod into an upright position without going too fast. Going too slow isn't an option either as it takes muscle to engage, just not too much muscle. It seemed as soon as I engaged it the head sawyer told me to disengage it. That or it would just run and run, and I would feel like I need to shut this down.

My impressions of the mill consisted of awe and respect. First, what waste of a log. The old cliche the guys tell me is for every board we cut, we donate a board to the sawdust bin. On Sunday, we cut a small ash log, and I think the whole room was coated in dust. Luckily, the dust is repurposed by a farmer for his animal pens. Still though, Bob Alt, our beloved volunteer and Board member, still had to sweep the windows today.

Second, the raw power of that blade. It really strikes fear into you when you see it just disintegrate the wood. It's amazing to see the sawyers struggle rotating a log on the cage, the carriage that carries the log into the blade, and then watch the blade treat the log like it was pudding.

Third, it took me a long time to be comfortable with the placement of the other sawyers. It shows you the training involved with the sawyers and the personal awareness needed by a sawyer. One needs to know his or her surroundings at all times and still be confident enough to employ tunnel vision to finish an aspect of the job. What I'm getting at is the blade needs to be feared enough but yet defeated enough that you can keep the blade clear so no real injuries occur.

Fourth, back to waste, one can see why particle board and various other repackaging of wood occurred. One is left with many tiny pieces, crooked pieces, and more oddities to get perfect slabs. Instead of just wasting the lower quality wood, companies found a way to use it. One day sawing shows you this need. I will never curse particle board again.